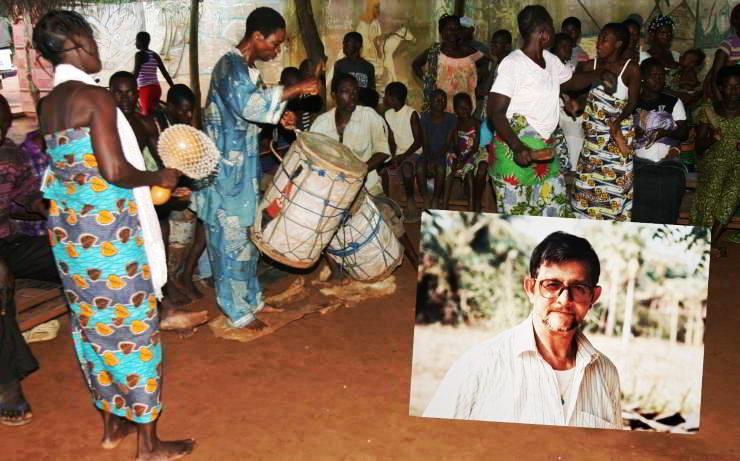

Italian anthropologist and Comboni missionary Father Bruno Gilli recounts 50 years of study of Voodoo, a West African religion that permeates every aspect of life and transcends definitions.

Beliefs that give rise to a complex religious system animated by forces that permeate every element of nature, mysterious witnesses to the connection between ancestors and the world. Forces that can punish and kill, as in the most widespread understanding of these beliefs, but that also inhabit humans and their potential.

A system that, over the centuries, has evolved, disintegrated, and distanced itself from its source. A trajectory that does not deny one fact, however, at the heart of Voodoo lies a secret. Father Bruno Gilli, anthropologist and Comboni missionary, spent decades penetrating it: not content with superficial explanations, challenging taboos, allowing himself to be guided in the deconstruction of preconceived ideas. Dedicating himself to researching the wonders and anxieties of this fascinating religious world.

How did you come to know about voodoo?

I first came across it in southeastern Togo in 1971, among the Wachi people, as a scholar and missionary. Over the course of about ten years, some of which I spent in France, I wrote my doctoral thesis on the issue of voodoo children, born with malformations or rare conditions that play a significant role due to their uniqueness. Then, also in Togo, I continued as a researcher, trying to uncover the mystery of initiation. And to do so, there was no other way than to witness the sacred rites. It took years. But I had met many adepts and discovered that there were no texts documenting their rites precisely. So, I set out to earn the trust of the initiatory community through a long and complex process.

How can we define Voodoo?

When you ask this question to a voodoo leader, they tell you they can’t answer because they’ve never seen voodoo. You need to change your perspective. This is because voodoo encompasses powers inherent in nature that operate but remain unseen. One could say they have been entrusted by the supreme entity, Mawu, to govern the planet. They are in the water, in lightning, in people’s minds. But not in the afterlife; only the ancestors are there. Even on earth, voodoo are forces governed by the ancestors through the divinatory agent called afà. They have the function of protecting and punishing, safeguarding the order of the world. They are indispensable for community cohesion. Voodoo is an Ewe word and a widespread concept in Togo, Benin, southern Nigeria, and Latin American countries.

There are at least three terms to define this “power”: the most common, voodoo, and the power of the hidden. Then there’s ayevhe, literally “cunning of the cavity,” which combines this original force with the human capacity to articulate it. And then there’s hu, which is also the mystery and the need to remain silent —a monosyllable that evokes the gesture made when someone can’t answer a question, resting their chin in their hands in an apparently “disconsolate” manner.

How has this practice evolved, but also across space? Voodoo is also present in the Caribbean and South America…

It has changed in its contact with the West and modernity, losing many followers. Previously, the initiation lasted three lunar years and could not be interrupted. Now the ritual has been reduced to a few months to allow young people to perform it during the summer holidays. Then the original voodoo, that of the ancestors, has been betrayed. The forces that regulate it have multiplied, often created arbitrarily by clans for reasons far removed from voodoo’s sacred origins. In Latin America, this religion has also merged with earlier beliefs, such as that of the Loa in Haiti. This has resulted in a degree of religious chaos.

Why is the idea of voodoo that has spread in the West so closely linked to terrible or violent elements, often manipulated?

Because authentic voodoo is unknown, but it is also the fruit of the crises of two societies. On the one hand, that of the new voodoo I just described, which is closely tied to appearances, sensationalism, and violence that the West so enjoys. On the other hand, there is the inability to imagine the Other without seeking the sensational, the obscure, typical of our Western society.

How do you see the relationship between Voodoo and Catholicism?

Today, there are many baptised initiates, but also many baptised individuals who return to voodoo because, they claim, the Christian God does not move, or does so slowly. There are many complexities, including historical ones: in Togo, the German colonisers banned voodoo practices, causing reactions and mistrust. Some rites also appear incompatible with ours.

There are some in which a community invokes the death of members of a rival clan. This certainly cannot be done by a baptised person. But, for example, this same practice, important for uniting group members, could be incorporated into the Catholic rite by removing this last part of the curse. Today, there is more dialogue.

For example, voodoo is closely tied to the heritage of communities and that of individuals. You cannot baptise someone without consulting their parents and finding out whether they were consecrated to a voodoo at birth…doing so without redeeming them would pose serious risks. The ancestor could take revenge.

Have you ever thought of undergoing initiation?

For a European, it wouldn’t make sense, for a simple reason: voodoo is rooted in our ancestors, and I have no ancestors who practised voodoo. That said, even when considering voodoo, I think Catholicism needs to purify its ancestral ritual. If this bond isn’t renewed, relationships are lost or deteriorate. Unfortunately, the West is losing its identity. (Brando Ricci)